Evert Oudendijck

One of a pair of Italianate landscapes:

a cavalry battle scene

Oil on canvas : approx. 58,3 X 69,4 cm

Signed lower right “E. oudendijck”

Sold at Sotheby’s Amsterdam, 9/05/06

For 19.200 €/the pair

This is a comparative item

Painting for Sale

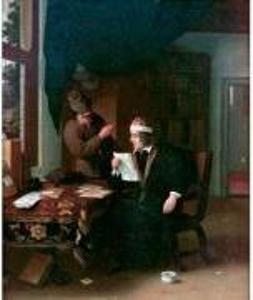

Oudendijck, Evert

"A doctor inspecting a flask of urine"

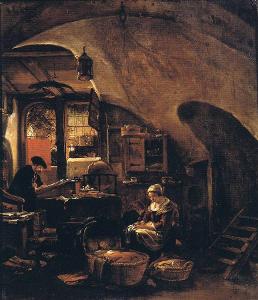

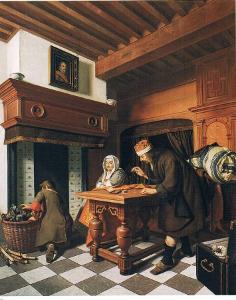

Comparative paintings

Click photos for more details