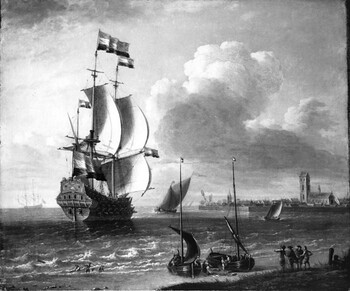

Laureys A. Castro

A Dutch East India man off Hoorn

Oil on canvas : 63,5 X 76,5 cm

Signed

London, Dulwich Picture Gallery

(black and white photograph)

This is a comparative item

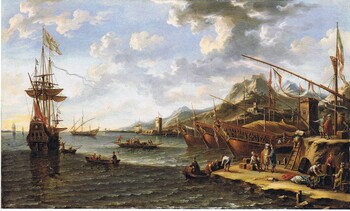

Painting for Sale

Castro, Laureys A.

"Two warships, a Maltese galley and an English Man-o-War"

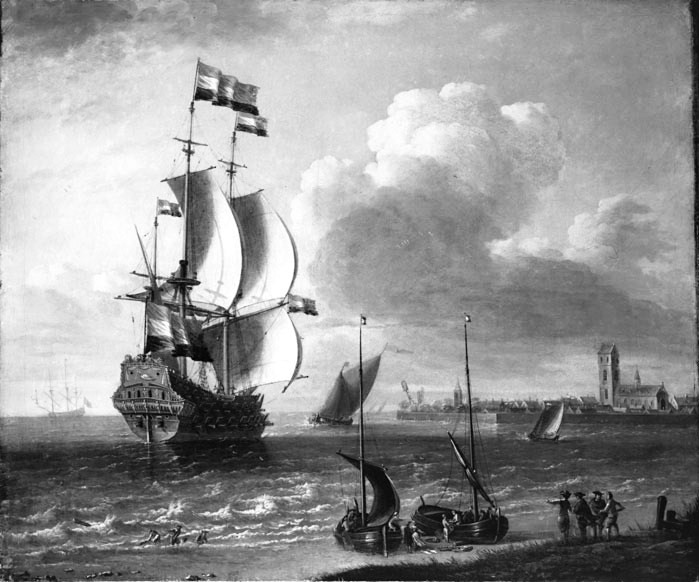

Comparative paintings

Click photos for more details